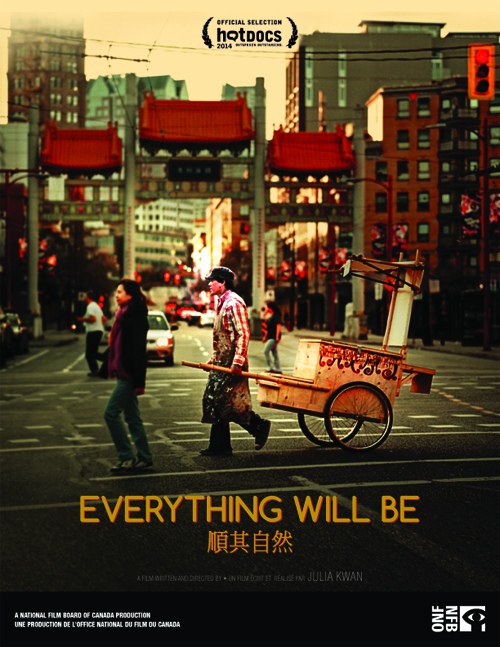

共有包括华裔执导在内的7部加拿大国家电影局(National Film Board of Canada)的纪录片,自4月24日至5月4日间,定于多伦多的“热门纪录片加拿大国际纪录片影展”中播演(Hot Docs Canadian International Documentary Festival)。今年所选纪录片包括两部世界首映电影,分别为曾获日舞影展(Sundance)奖得主的电影制作人Julia Kwan,所执导的纪录片“Everything Will Be”,将于多伦多首映;另有曾四度获艾美奖(Emmy),也是多伦多热门纪录片喜爱的导演John Kastner,带着纪录片“Out of Mind, Out of Sight”在多伦多首映。

下面是关于该片的英文介绍以及与Julia Kwan的问答。假若你想先睹为快,请留言此文,我们将为你提供对应链接及其密码,你就可以观看全片。

As dawn breaks and most of the city still sleeps, the long-time merchants of Vancouver’s Chinatown are hard at work. They haul out their produce stands and set up their make-shift vendor carts in preparation for what they hope will be a busy day. But, like many ethnic enclaves in urban centres across North America, their clientele is dwindling. This once vibrant and thriving neighbourhood is in flux as new condo developments and non-Chinese businesses move in and gradually overtake the declining hub of the Chinese community.

Everything Will Be, from Sundance award-winning director Julia Kwan, captures this fascinating transformation through the intimate perspective of the neighbourhood’s residents, diverse merchants and new entrepreneurs who offer their poignant reflections on change, memory and legacy.

A public art installation erected on the roof of a local real estate mogul’s contemporary art gallery – housed in one of the oldest buildings in Chinatown – illuminates in neon the words “EVERYTHING IS GOING TO BE ALRIGHT.” Night and day, this sign looms over Chinatown. Everything is going to be alright. The big question is – for whom?

Writer and Director – Julia Kwan

International award-winning filmmaker Julia Kwan is a writer, director and producer living in Vancouver, B.C.. Her feature film debut, Eve & the Fire Horse met critical acclaim after premiering at TIFF and Sundance where it won the Special Jury Prize for World Cinema. It also garnered Ms. Kwan the prestigious Claude Jutra Award for Best First Feature Director, received five nominations at the Genie Awards, and was chosen as one of ten films in Indiewire’s Undiscovered Gems series. Ms. Kwan has two features in development: The Slave Girl and Portraits of You and Me, chosen for Tribeca’s All Access Lab. Everything Will Be marks Ms. Kwan’s feature documentary debut.

Producer / Executive Producer – David Christensen

David Christensen is the executive producer of the National Film Board of Canada’s North West Centre, responsible for documentary, animation and interactive production in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, the Northwest Territories and Nunavut. His recent work includes the NFB-co-produced feature documentaries Wiebo’s War, and We Were Children, the Oscar-nominated animated short film Wild Life, the interactive website Bear 71, as well as emerging filmmaking programs for Nunavut filmmakers.

Q&A with filmmaker Julia Kwan

What’s the history of Vancouver’s Chinatown?

Vancouver’s Chinatown was a Chinese ghetto that was born out of necessity and oppression when the Chinese were brought over to assist in the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway. Not welcome in any neighbourhood, they created their own, and over the years Chinatown thrived and grew into a vibrant community.

In the 1970s and ’80s, Chinatown had lots of foot traffic. However, shifting residential and economic patterns of the Chinese community in Vancouver have taken its toll on the neighbourhood. As well, the decline of Vancouver’s Chinatown is a result of its close proximity to the Downtown Eastside neighbourhood, often noted for a high incidence of poverty, drug use, prostitution, crime and violence.

Reviews of Vancouver’s Chinatown on TripAdvisor are overwhelmingly negative: “Avoid it”; “Stay away”; “Too many shady people around”; “Very seedy area of town”; “The local people were homeless, drug addicts or prostitutes”; “A sad joke on tourists that do not know better”; “I wish I had listened to the locals and not wasted my time”; “If you like the ghetto, you’ll love Chinatown.” In the face of the harsh criticism, shopkeepers try to endure.

Another reason for the area’s decline is the emergence of satellite Chinatowns in suburbs like Richmond. The suburban malls offer similar products to Chinatown, but they are perceived to be in a cleaner and safer space with easier and/or free access to parking.

Unlike Richmond, Chinatown has a rich history, with the early immigrants coming from rural areas in southern China and putting down working-class roots. A majority of the Chinese people who work or live in Chinatown speak Cantonese, and for many, it is their only fluent language. It is a community built on economic and social marginalization.

In recent years, Chinatown has become a community in flux. It has suddenly become a hot, trendy destination for art galleries and new businesses catering to condo dwellers.

Can you talk a bit about the visual look of the film? What was your inspiration?

The look of the film was very much inspired by the images of Vancouver photographer Fred Herzog, who took candid photos of street life in the ’50s and ’60s. Like Herzog’s Kodachrome images, the images in the film are vibrant—the blacks are deep and rich and mysterious, and the Asian reds are vivid and pop amongst the other colours. Herzog found the locals of the older, east-end part of the city more expressive and uninhibited than the people from more affluent neighbourhoods. Like Herzog, I wanted to capture the grittiness (the distressed walls, worn-out signs) and humanity through a thoughtful and compassionate eye. Of course, the grittiness is awash with Herzog’s warm, Kodachrome glow.

You’re from Vancouver. What’s your personal connection to Chinatown?

When I ponder my childhood, I only remember my father ever wearing one outfit: white dress shirt, black slacks. He wore this outfit for the majority of my childhood and his closet overflowed with these two items. He only became “colourized” 15 years later, when he left his job as head waiter at Ming’s Restaurant, a hot, bustling establishment in Vancouver’s Chinatown. As a child, I spent a lot of weekends in Chinatown. I remember the greengrocers bellowing the names of the imported fruits, the throngs of people as I negotiated my way through the crowds, the sounds of mah-jong tiles and opera rehearsals drifting out of the windows from the recessed balconies of the benevolent societies. My Chinatown was seen through the nostalgic lens of childhood. Making this documentary was my reaction to the shuttering of many well-established Chinese businesses in Chinatown, the sudden development of luxury condos and the influx of new, non-Chinese businesses. As I started to make the documentary, I had to re-evaluate my own feelings about the community. Despite my great affection for the community, I realized that I rarely ever go to Chinatown anymore and had to examine my current relationship with it. It is through the making of this documentary that I discovered the real heart of the community.

How did you select the characters?

Everything Will Be offers a unique look into this exclusive world. We meet individuals who are the most unlikely—and sometimes, unwilling—documentary subjects. It is a privileged glimpse into a closed community.

Instead of focusing on the activists and the scholars, I wanted to shed light on the people who live and/or work in Chinatown—the ones who don’t show up at the town meetings. The only exception is Bob Rennie, a prominent real estate marketer, who has become a significant figure in the Chinatown community. Otherwise, the subjects are the quiet majority, whose sole focus is day-to-day survival. Their voices have been all but absent in discussions about the changes. The film is filtered through their eyes as we see the small yet pervasive ways these changes have permeated their lives and their livelihood.

In fact, the most common thing that I heard during my interviews with shopkeepers was their insistence that they were not special or worthy enough to be the subject of a documentary. Getting the Chinese community to participate in the film was the hardest task.

Everyone said the same thing: “There’s nothing special about us, we’re just ordinary people, why do you want to film us?” It is because of this attitude that it is important to focus on them. It is about finding something extraordinary in the “ordinary,” like the characters in an Alice Munro story. It took us almost a year to convince Mr. and Mrs. Lai, the herbalists, to participate in the film. We even hired their daughter as a P.A., and for a while they still said no. We had to basically wear down the subjects with our tenacity and iron will.

Did you have an opinion about Chinatown’s transformation, and if so, did that opinion change after making the film?

For me, the purpose of making this film was not to offer any solutions or provide any answers to the complex issue of gentrification. Instead, I want the film to act as a catalyst to start a dialogue about these issues and give viewers an insider’s perspective on how the change has affected the locals.

What was the most surprising perspective you heard while making the film?

The most surprising perspective to me was the one of the tea shop owner, Olivia. The whole film is a meditation on memory, preservation of culture and legacy, but Olivia talks about the act of letting go and expresses the futility of embracing memory.